Hype and sensationalism sell headlines like nobody’s business these days.

Part of my reason for wanting to explore ackee in a positive light was this very reason. It seemed poison, toxic and deadly would always be plastered somewhere in the text wherever ackee was concerned.

Now I am not here to downplay the fact or deny that there are circumstances under which ackee is poisonous, but rather to discuss the concerns of toxicity in a logical manner. I will simply present the evidence we have gathered from science so far devoid of all the common eye-roll inducing clickbait tactics.

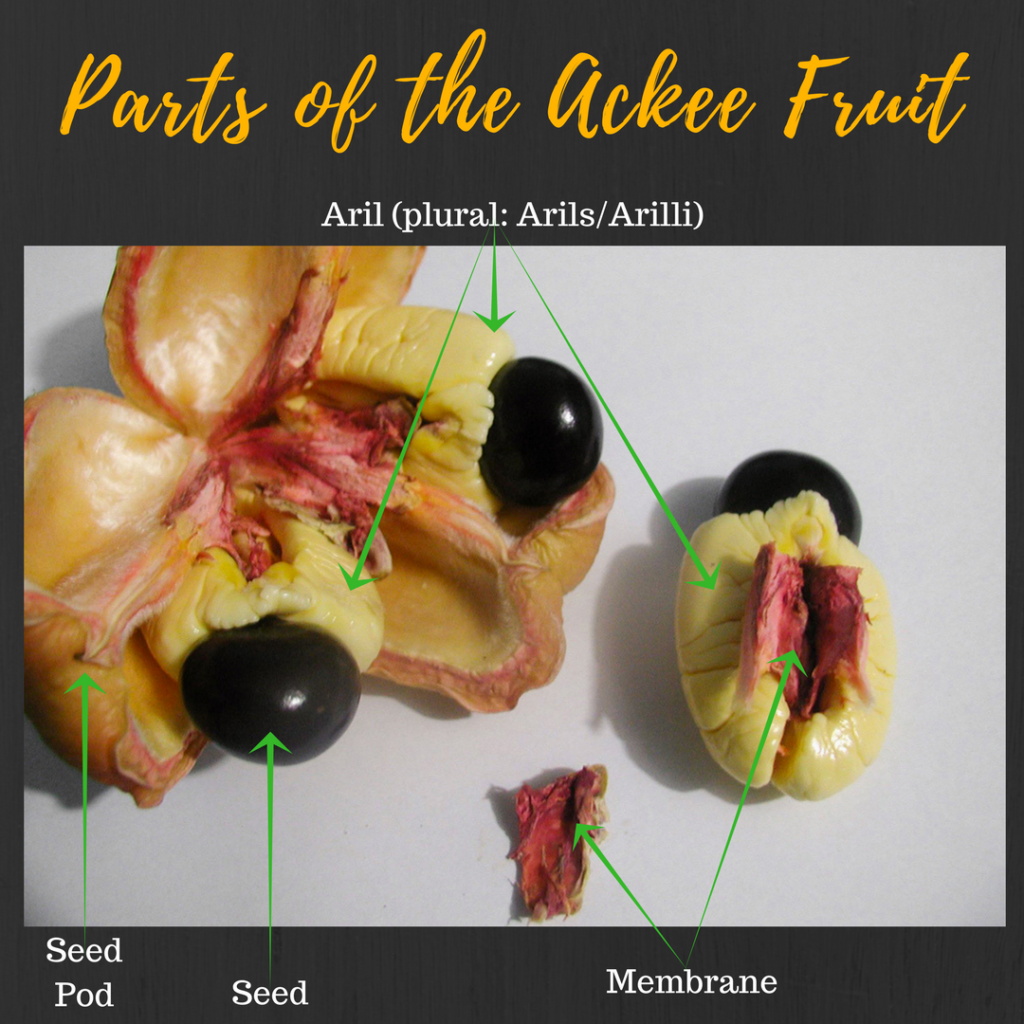

Before we get started let’s take a look at this picture of the parts of the ackee fruit again for reference:

Ackee Toxic?

From at least the 1880s there were recorded reports of an illness dubbed ‘Jamaican Vomiting Sickness’ (JVS) Syndrome. Though the correlation between the illness and ackee was known, it was not known exactly how it was caused since ackee was being widely and safely consumed. The illness is now called Toxic Hypoglycaemic Syndrome:

“Symptoms occur 6-48 hours after ingestion of unripe ackee arils and include nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, muscular and mental exhaustion, and hypoglycaemia (rapidly reduces blood glucose to extremely low levels). Young children have been known to die within a few hours of ingesting unripe ackee arils. Treatment has to be quick, within hours, and although there is no standard method of treatment, early sugar and glucose administration is recommended (Goldson 2007)”[1]

What is Hypoglycin A & B?

Hypoglycin A & B are both amino acids; you know the stuff that proteins are made up of? Building blocks essential for all metabolic processes and all that jazz. See, it’s not so scary when we discard the hype.

Hypoglycin A & B however are unusual amino acids having a toxicity similar to ‘Jamaican Vomiting Sickness’ Syndrome, and so the link was found.

What Parts of the Fruit are Poisonous and Under What Circumstances?

Only the aril of the fruit is fit for consumption.

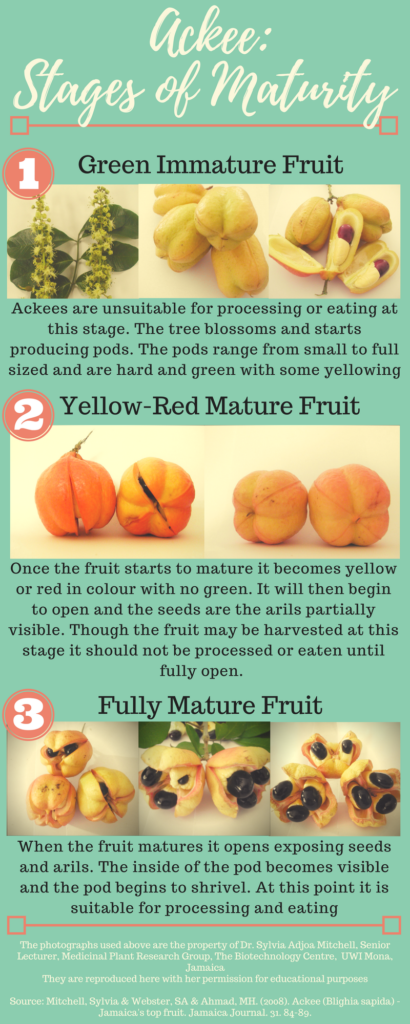

Further, only the arils of ripened/mature ackee should be eaten or processed for packaging (more on this later).

Arils of the unripe fruit contain hypoglycin A in high amounts, the amounts diminish (13-fold) as the fruit matures and when it is cooked. Therefore the aril of the fruit is only poisonous if eaten when unripe or improperly prepared.

The seeds of the ackee contain hypoglycin B. It is present in lesser amounts when the fruit is immature and increases (7-fold) as the fruit matures. The seeds of the ackee therefore are always poisonous and should never be consumed.

It is not clear if the membrane is always poisonous and therefore it is always discarded in the cleaning of ackee and considered not suitable for consumption.

Preparing Ackee Safely

Exposure to the sun reduces the level of hypoglycin A in the aril of the fruit. Boiling the arils also reduces the hypoglyin A to levels that are safe for consumption, this is because hypoglycin A is water soluble. The recommendation given is that the cooking water that the ackee arils are initially boiled in should be discarded.

Interestingly in another paper [2] I read, it is noted that the ripe ackee arils are edible and can be eaten fresh, dried, fried, boiled, roasted or made into sauce or soup. For this paper, the ackee had been washed thoroughly after harvesting then dried. Both full fat and defatted ackee flours were studied, I’ve provided the source to that paper below.

If you have access to fresh ackees, simply be smart and only harvest mature pods. Do not force unopened ackees open.

As the old riddle goes:

“Me fader send me to pick out a wife; tell me to tek only those that smile, fe those that do not smile wi’ kill me” [3]

Translation: “My father sent me to pick out a wife, he told me only to take the ones that smile, for the ones that do not smile will kill me”

The riddle speaks to ackees toxic nature if selected before it is mature, the smiling here refers to the ackee pods opening naturally and exposing the seeds and arilli.

Ackee Banned?

Ackee has been exported from Jamaica since the 1950s. In 1972, the FDA effectively imposed a ban on canned ackee coming from Jamaica. This ban was placed in effect due to the possible toxicological effect of hypoglycin A in the fruit. An upper limit of 100mg/kg was of hypoglycin A was placed on canned ackee.

“Ashman (1991) reported a reproducible analytical procedure capable of detecting hypoglycin A in the arils and brine of canned and unprocessed ackee to a detection limit of 0.1 mg/100 g fresh weight. This work provided the basis for the successful defense for the conditional re-entry of direct ackee export into the USA market in 2000 thus lifting a 27-year ban and ackee exports to the USA resumed. Presently only certified agro-processors, with food safety controls (HACCP) in place, can export ackee that will not automatically be detained (see FDA Import Alerts 2000)” [1]

Exports to the US were once again briefly suspended in 2005 but have since resumed. Export destinations include over 20 countries including the US, UK and Canada (pretty much anywhere you can find Jamaicans in the diaspora, so soon EVERYWHERE!!!! 🤣🤣🤣)

Processing of Ackee

As one of our major exports, care is taken to ensure safety in the production process.

“This ripening process has to be documented and controlled as part of the entire production process and monitored by the Bureau of Standards as stipulated in the Processed Food Act of 1959 and as part of the Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) system of production by JS 276:2000: Jamaican Standard Specification for canned ackee (Blighia sapida) in brine (RADA 2006b). The Bureau of Standards Jamaica has developed a scale and colour chart – ‘Ackee Maturity Index Chart’ to illustrate the ripening process and to indicate when the fruit are ready for reaping (BSJ 2006)” [1]

You can rest assured that your canned ackee went through a thorough inspection process before getting to you. Does it mean there will never be any incidents ever again, as with the unpredictable nature of life in general this isn’t a promise that can be made, however, a system is in place to try to prevent anything untoward from happening as best as possible.

If you’ve made all the way to the end I’d like to thank you for sticking through with me, this is indeed one of the longest posts on this site! I hope you found it informative and possibly learned something new as did I while doing the research. Finally, if you had fears or concerns regarding ackee I hope that I’ve helped assuage some of them.

Thanks for stopping by, until next time 😊

Photos used and credited above are the property of Dr. Sylvia Adjoa Mitchell, Senior Lecturer, Medicinal Plant Research Group, The Biotechnology Centre, UWI Mona, Jamaica

They are reproduced here with her permission for educational purposes.

To read the full paper, click here to access the link to download it on Researchgate

[1] Mitchell, Sylvia & Webster, SA & Ahmad, MH. (2008). Ackee (Blighia sapida) – Jamaica’s top fruit. Jamaica Journal. 31. 84-89.

[2] Dossou, Veronica M., et al. “Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Full Fat and Defatted Ackee (Blighia sapida) Aril Flours.” American Journal of Food Science and Technology 2.6 (2014): 187-191.

[3] John Rashford. “Those That Do Not Smile Will Kill Me: The Ethnobotany of the Ackee in Jamaica.” Economic Botany, vol. 55, no. 2, 2001, pp. 190–211. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4256421.